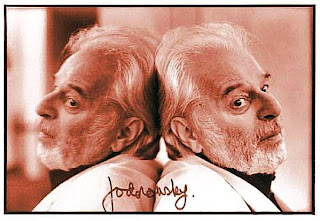

Born in Iquique, Chile, in 1929, Jodorowsky showed an early interest in both performance and poetry. Published in Chile at the age of 16, he was well respected within the South American poetic community by the time he developed a talent for puppetry and mime. After joining a French theatre troupe, led by renowned mime Marcel Marceau, Jodorowsky toured Europe, writing plays and making vast connections within the artistic community. Bizarre projects in both Mexico and France followed, with Jodorowsky developing a following of students and fellow performers in the late fifties and early sixties. Jodorowsky’s eclectic mix of innovative physical theatre and spiritual mumbo-jumbo worked its way into his theatre projects, and soon El Panico, a mixture of comic-strip art, physicality and avant-garde improvisations was created. This movement added to Jodorowsky’s already impressive roster of theatrical achievements, having directed touring productions of the works of Ionesco, Beckett, and Strindberg throughout France and South America.

It was during this time of the early 1960’s that the ever-strange Jodorowsky began to dabble in the occult, relying heavily on tarot cards and mystical omens that would figure so heavily in his film work.. Wikipedia labels Jodorowsky as one of the leading practitioners of “psychomagic,”a strange combination of psychology and occultism, meant to heal mental wounds. With these beliefs, along with his chaotic, if convicted theories on live theatre, Jodorowsky cut a swathe through the more conventional theatre experiences of his time. Influenced heavily by surrealists such as Antonin Artaud, Jodorowsky pummeled his audiences with crucified chickens, topless murderesses, malodorous vaginas and personal violence.

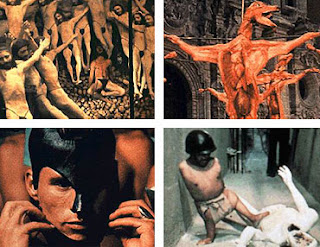

His first feature-length film, Fando y Lis debuted in 1968, and claimed to deal with social and political issues affecting Mexico. The film had its premier in Acapulco, and worried promoters were justified in their anxiety when a riot broke out in the cinema. Based on the play by Fernando Arrabal, Fando y Lis is a complicated jumble of religious imagery, deranged sexual miscreants, road movie motifs and violence, all sorts. In short, a typical Jodorowsky outing. The principle objection Mexicans had to this incendiary film was that it had a corrupting influence on Mexico’s youth culture. Now, Jodorowsky may be no Socrates, but a wheel-chair bound woman squirting piglets out of her vagina is certainly bounds for controversy, if not death by hemlock.

Not surprisingly, Fando y Lis was not Jodorowsky’s first foray into film. Just last year his 1957 short La Cravate was discovered in an attic in Germany, to loud cheers and jeers by the artistic community. Jodorowsky himself had long considered this work to be lost, but since its rediscovery, has spoken out in praise of this early experiment, something he is not always wont to do with work he is displeased with. But more on that later. La Cravate was filmed during Jodorowsky’s early touring days and shows how heavily influenced the young director was by his involvement with mime. Shot without sound, it shows the existential experiment of one young woman as she forces a young man and a boxer to change heads, exhibiting one of the director’s pet loves, a sort of blood soaked incorporeality, with lessons about vanity and materialism thrown in for good measure. The film was essentially forgotten, and like Fando y Lis, buried under a heap of protestations and controversy.

All was not lost for the burgeoning filmmaker, as the notoriety gained from the spiritual and artistic assault that was Fando y Lis gained him a small cult following of the best kind: rich celebrities. John Lennon and Yoko Ono, fans of the first feature, offered to help finance Jodorowsky’s next outing, and hooked the director up with the Beatles’ accountant, Allen Klein. The result was that ABKO Films produced the weirdest, most psychedelic, feral, and explicit film of its time, Jodorowsky’s heart stopper, El Topo. Heralding the beginning of the man’s tenure as “King of Midnight Movies,” El Topo chronicled the desideratic journey of one man, (accompanied by his naked son, perched atop his shoulders, naturally,) as he navigates the confused, decadent, and sinful landscape en route to defeating his enemies in cataclysmic gun battles. Part philosopher, part mystic, part murderer, all man, El Topo sways into dusty towns, rabbit-strewn hermit-holes, crumbling adobe towers, what have you, and shares with the earthy inhabitants ( who, also quite naturally, often include naked women,) either his wisdom or his bullets. A particularly bright piece of satire appears when, in a crowded church, a gun is passed around to each member of the congregation. Each time the hammer clicks in place and no bullet is disgorged, the ecstatic church-goers shout out a frenzied “it’s a miracle!” and eagerly hand the gun to their neighbour for the next test. One man points out that the bullet is a blank, and so replaces it with a real one. A hushed awe comes over the crowd as a woman is handed the gun, and cocks it back. When it is fired and the action proclaimed a miracle, the gun is then handed to a child who promptly fires the loaded chamber into his brain and dies. What this loaded piece of ridicule does is enrich the otherwise rambling, episodic and mostly ambiguous nature of El Topo with a short, sharp slap of reality. More than that, this moment is very, very funny, and in the midst of so much sex and violence, speaks to Jodorowsky’s skill as the strangest man in cinema, more satyr than satirist.

The Holy Mountain, Jodorowsky’s next film project, begins with a ritual, and ends with an enlightening practical joke. Released in 1973, the director had approached John Lennon, by now a friend as well as fan and financier, to take the starring role of the character billed only as The Thief. An even more brazen outing, The Holy Mountain details the messianic journey of the lead character as he, and other chosen disciples, culled from their respective mystical states and distant planets, are led to the path of immortality by The Alchemist, played by the maestro himself. To prepare himself and his cast, including his wife, Valerie, for the craven vortex that would be filming The Holy Mountain, Jodorowsky reputedly engaged in prolonged LSD use in combination with several ascetic and Buddhist experiences, the more to get into the mindset that the film would require. Once completed, the film debuted at Cannes, and was put out on limited release by the cautious Allen Klein. Hippies and underground art lovers loved it, but its exposure was too limited and its fans too diverse. It all but bombed.

Still, Jodorowsky’s boundless enthusiasm and energy had him already working on another project, his doomed Dune adaptation. Among the startling casting choices were Gloria Swanson, Brontis Jodorowsky, ( the director’s son,) and none other than Orson Welles. A rabid support base among the alternative art crowd had conceptual artists like H.R. Geiger and comic artist Moebius signing up to do set and costume designs, but ultimately, the people with money were in less supply and the film, though going through several incarnations on the page, was never to be produced.

Other, more banal projects followed, but the elements of critical failure, artistic disenchantment and lack of popular support led to films like Tusk(1979), Santa Sengre(1989), and The Rainbow Thief (1990),which terrifyingly stars Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif, and was the first film

that Jodorowsky directed that he did not write, all failing to get responses like those of Jodorowsky’s earlier films. These films have largely been disowned by the filmmaker, and most collectors would not include them in the cannon. Devoting his time now to creating comics and collaborating with old friend Moebius, Jodorowsky has once again hit the circuit as the first-ever DVD releases of his first four films were released earlier this year, after a protracted legal battle with ABKO. Once again, his surreal mix of spirituality, questing weirdos, bloody-mindedness and fecund sex are available for all and sundry to marvel at and decry. The man who married Marilyn Manson and out-weirded Denis Hopper is here for a whole new legion of outcasts, lovers, sinners and cinephiles. Beware.

that Jodorowsky directed that he did not write, all failing to get responses like those of Jodorowsky’s earlier films. These films have largely been disowned by the filmmaker, and most collectors would not include them in the cannon. Devoting his time now to creating comics and collaborating with old friend Moebius, Jodorowsky has once again hit the circuit as the first-ever DVD releases of his first four films were released earlier this year, after a protracted legal battle with ABKO. Once again, his surreal mix of spirituality, questing weirdos, bloody-mindedness and fecund sex are available for all and sundry to marvel at and decry. The man who married Marilyn Manson and out-weirded Denis Hopper is here for a whole new legion of outcasts, lovers, sinners and cinephiles. Beware.

No comments:

Post a Comment